Fish Story Memphis; Memphis is the center of the world

by Aviva Rahmani

Journal for Environmental Studies and Sciences Vol. 4 (June 2014): 176–179

Abstract

In this article, artist Aviva Rahmani describes her methodology for an ecological art project about environmental restoration in Memphis, TN. The City of Memphis attracted her because it is in the middle of the third largest watershed in the world on the Mississippi River, the sixth largest river on earth. Fish Story, was a transdisciplinary collaboration with paleoecologist Dr. James White and wetlands biologist Dr. Eugene Turner for Memphis Social, a city-wide exhibition. The project launched May 4, 2013 and culminated with an installation that opened to the public May 11, 2013. It was a test for Rahmani's Trigger Point Theory, an approach to environmental degradation that locates nucleation sites to catalyze bioregional restoration for large degraded ecosystems. The Fish Story goal was to identify Trigger Points in Memphis and explore their activation. Fish were identified as an iconic taxa, whose welfare reflects the welfare of the waters humans depend upon. As fish go, so go people. The story of fish is the story of our human future.

Fish Story Memphis

As an ecological artist, I take responsibility for scientific competence in my experiences as an Affiliate at the Institute for Arctic and Alpine research (INSTAAR), University of Colorado at Boulder (UCB), as a researcher with the Zurich-Node group of the University of Plymouth, United Kingdom, and in completing a certificate in Geographic Information Systems with City College of New York. I have worked to redefine public art to include personal accountability to bioregions and environmental justice. That is a form of social practice in relation to the environment that I call “performing ecology.” My work includes creating transdisciplinary1 strategies to engage constituencies, finding points of leverage for large landscape ecosystem problems, that I call Trigger Points (Rahmani 2012) and discovering new knowledge from these processes. My aim is to effect resilience for water and habitat in the Anthropocene.

1990-2000, I completed my environmental restoration project, Ghost Nets.2 It became the basis for my current research practice and is a case study for my dissertation, “Trigger Point Theory as Aesthetic Activism.” Additional large scale restoration projects have included Blue Rocks which led to the restoration of 26 acres of wetlands in 2004.3 Ghost Nets also led to my project for Memphis, Fish Story, the second case study for my dissertation. The content of Fish Story evolved from, Gulf to Gulf (2009- present, publically available as a series of raw webcast mini-think tank recordings)4 which has examined the relationships between global warming and gulf regions internationally. Gulf to Gulf's core group has been a small team of scientists and myself. After the BP spill in the Gulf of Mexico, we dedicated our time to strategizing ways to deal with connections between the impact of extractive industries and climate change. Fish, such as micropterus dolomieui in river systems (Hilty, Merenlender 2000), are an indicator taxa for environmental disruption. We began focusing on how fish habitat might indicate where to intervene in large systems such as the Mississippi Basin watershed, which became Fish Story. Our work is fiscally sponsored by the New York Foundation for the Arts (NYFA), enabling us to raise money as a tax deductible project. This article will discuss Fish Story in more depth.

In 2012-3, at the invitation of curator-artist Tom McGlynn, co-founder with Bill Doherty of “Beautiful Fields”5 (awarded the domestic 2013 franchise support grant from apexart) our team created Fish Story for Memphis Social, for three weeks in May 2013. “Beautiful Fields” is a team of artist-curators who assembled exhibitions to “address the notion of the social as both context and subject.” “Memphis Social” was a city-wide group exhibition of works about social context (Koppel 2013).

My plan for Fish Story was to create a public art project to engage people in the conservation and restoration of waterways. I hoped that following the fortunes of fish might help us locate at least one restoration trigger point that could effect larger changes (Rahmani 2012). Memphis is the center of the world symbolically and continentally.6 It is significantly located along the Mississippi River. The Mississippi River Basin watershed serves 18,000,00 people,7 is the third largest in the world, but is heavily polluted by factory farming upstream. That pollution contributes to dead zones in the Gulf of Mexico downstream (Burkholder et al. 2007). The city of Memphis has been characterized as a racially divided, economically depressed community in which large numbers of young people have little access to opportunity or quality education. These factors make it a paradigm for the kinds of global circumstances and conflicts that affect water quality worldwide. Our goal for this project was to find new knowledge about resiliency for Memphis riparian zones, watersheds, animals and people. We conjectured that research towards implementing this project would support our observations that the local river tributaries would be where we might find our Trigger Point.

I based Fish Story on the premise that talk alone doesn’t solve the kinds of urgent environmental challenges we face today. Some knowledge about solutions comes from body experience, especially in contact with others (embodiment). Some comes from meditation. Some comes from our senses, e.g., listening to sound, activities or working with soil and plants. And some comes from talking. This holistic approach is shared by many who are part of an embodiment movement that goes back to John Dewey’s (1938) work.

Developing Fish Story from Gulf to Gulf, culminated three years of work. My collaborators included Dr. R. Eugene Turner,8 ecologist and Distinguished Research Master and Professor, Department of Oceanography and Coastal Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, Dr. James White,9 paleoecologist, Professor of Geological Sciences, and Director of INSTAAR at the University of Colorado at Boulder and others, to identify where we can intervene in ecological devastation. Fish Story, was the first on-the-ground application of our thinking. In 2012, James Bradley, executive director at WebServes10 joined the team as our technology consultant and is presently developing an educational website for students of wetlands restoration, based on this project.

When we decided that fish were the way into the larger issues we wanted to address, we launched the project in October 2012 by inviting people to share their personal fish stories for the Pushing Rocks blog.11 Fish were chosen because for many people, the life of a fish is as invisible as the source of their tap water. On my blog, I wrote about other topics that fish seemed to parallel. I linked human homelessness and dying fish. They both reflect symptoms of dysfunctional systems that have sacrificed many human and non-human lives. Fish Story worked to increase awareness towards restoring degraded ecosystems. It was about global warming: knitting bioregions and connecting dots to environmental justice, one critical location at a time.

Here was my fish story:

I remember the only time my Father invited me go fishing with him. It was a sunny, warm day. I was four. In our rowboat out on the water, he had a can of worms, from which he pulled a fat candidate with one hand, while lifting a hook with the other. Suddenly, I realized he meant to thread the sharp, steel point through that small, soft, helpless creature's body and I began shrieking, sobbing uncontrollably and inconsolably, as, shocked and confused, he stared into my face. That was how I first learned where dinner came from.

As an artist, I designed four phases of activity for Fish Story for Memphis in May, to build on and offer different approaches to considering regional water. Participants were invited to enter or exit the project from several locations, platforms and events.

Fish Story for Memphis began May 4th with a canoe trip. I trained for several months in preparation for that event, despite health issues, regarding it as an “endurance event,” paralleling what I believe the Anthropocene requires of us all. Dr. Turner and I started our canoe trip at the end of the Ghost River where the Wolf River begins, which then feeds into the Mississippi River. We were accompanied by six river guides from the Wolf River Conservancy, who were charting that section of the river for the first time. The Ghost River is an ecosystem replete with poisonous snakes and beautiful bottomlands wilderness but struggling to recover from clear-cutting and invasive privet. The Wolf River continues through a series of contrasting city demographics to where the tributary was diverted by the Army Corps of Engineers where it should reach the Mississippi.

Participatory mapping is a way to visualize how things fit, from water to despair. On May 7th, I led a workshop at the Crosstown Arts Gallery to produce participatory maps that would contribute to a larger public installation at the Memphis College of Art.

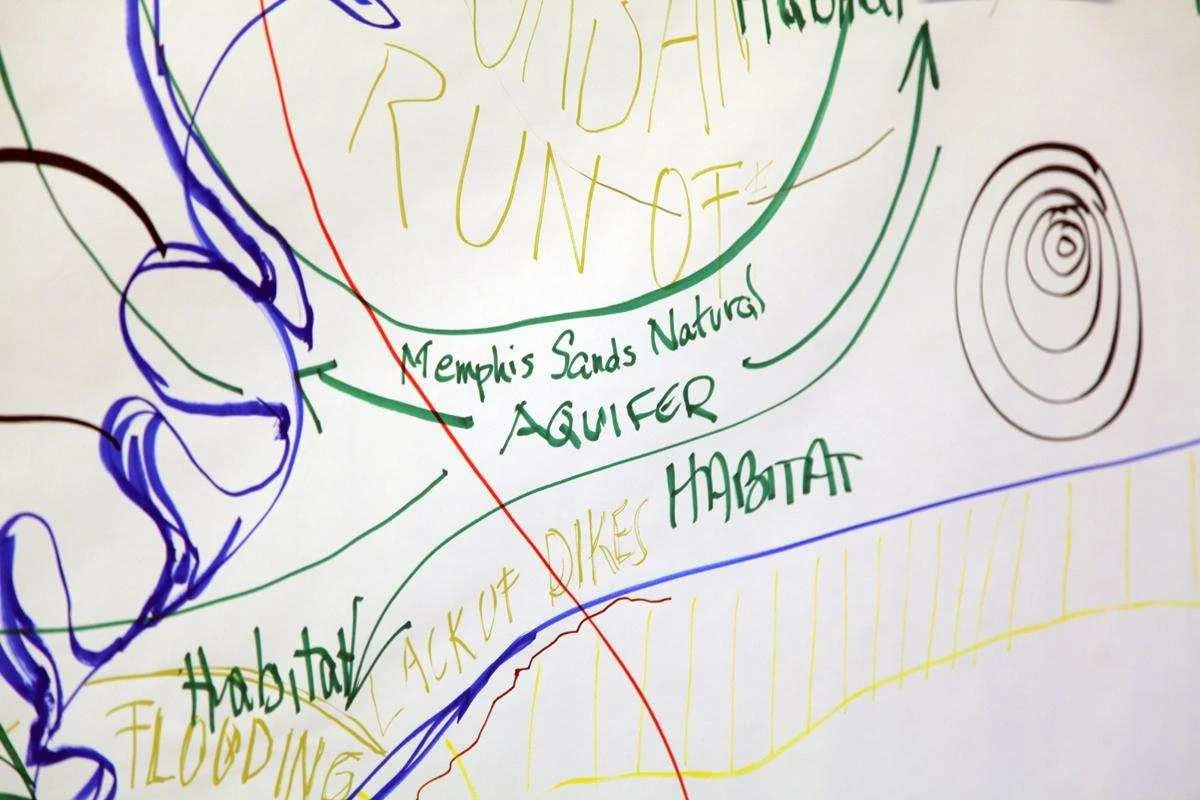

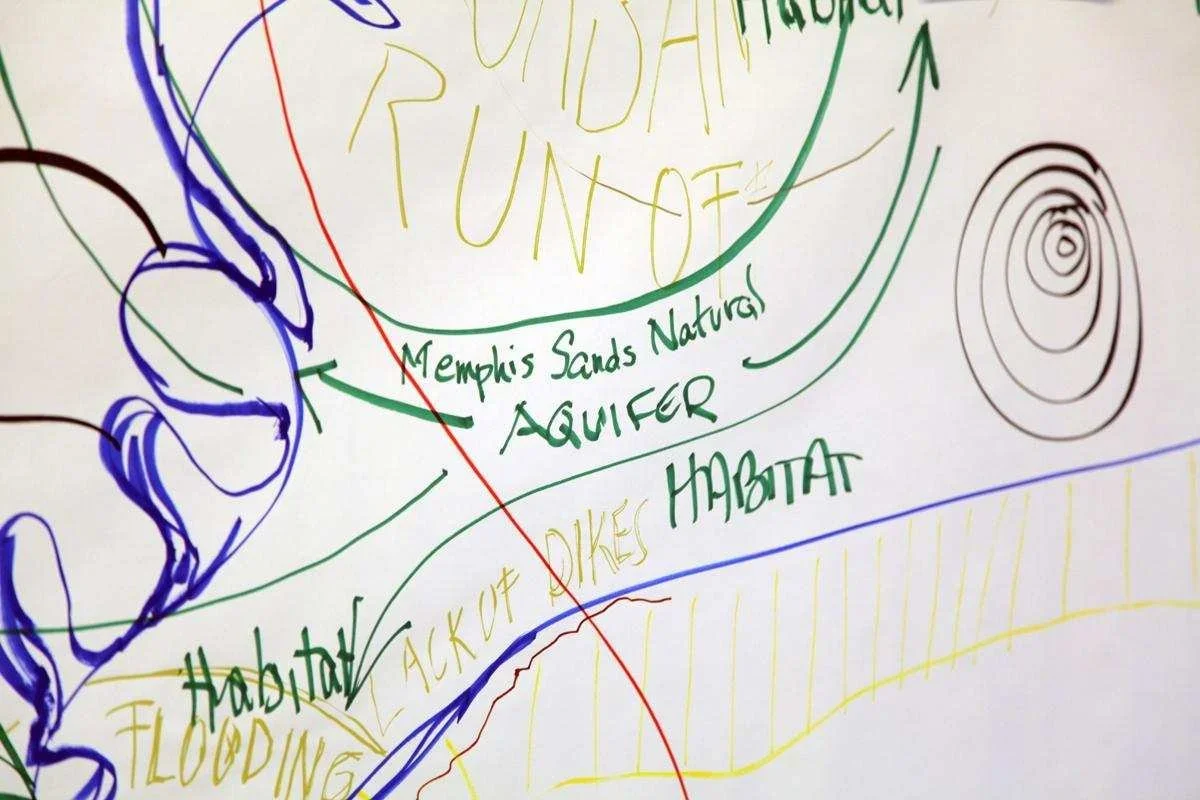

Participants were asked to play the “Anthropocene Game,” an exercise in role-playing causes of environmental degradation, to spend a short period in meditation and listen to a song before they began the mapping. (See Fig. 1 and 2 detail of the resultant participatory mapping).

9 See http://instaar.colorado.edu/people/james-w-c-white/10 10 See http://webserves.org/ 11 See http://www.ghostnets.com/blog.shtml 12 For impacts of Hurricane Sandy on New York City see http://www.nyc.gov/html/recovery/downloads/pdf/sandy_aar_5.2.13.pdf 13 Discussion of New Yorkers concerns about fracking can be seen here http://blogs.plos.org/publichealth/2013/06/18/what-is-the-health-impact-of-fracking/ 14 Vocalist Aviva Rahmani accompanied on piano by Debra Vanderlinde. Recording can be heard here http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=irQtqnCuZUE 15 That correlation was developed between White and myself for Fish Story, May 2013. 16 Recording of "Connecting the River Dots" can be found here https://vimeo.com/67578327 17 See http://meld.cc 18 See http://evelaramee.com/ 19 See http://www.ruthhardinger.com/

Fig. 1 6' x 30' participatory map generated from The Anthropocene Game for Fish Story

Fig. 2 Detail of 6' x 30' participatory map from playing the Anthropocene Game

I had first created and tested The Anthropocene Game at the Gasser Grunert Gallery in New York City, January 21, 2013 to address the effects of Hurricane Sandy 12 and concerns about fracking. 13 Sandy was one symptom of a new phase of environmental change confronting humans with new challenges. The “game” was designed as an experiment in employing embodiment techniques between strangers to find new knowledge. As in Memphis, a meditation took place after the game and before a group discussion. During the meditation for both events, I sang an acapela French art song, “Au Bord de L’Eau,” by Gabriel Faure to the group.14 The song line sounds like running water. I believed it evoked a state of mind that could leave the group open to thinking differently. During the playing of the “game,” physical contact was encouraged under controlled rules, to express the dominance on future events of one influence or another.

My premise for singing the song was that how we come to observation, is framed by every aspect of our consciousness. I believed the sensual experience of listening to music like water, filtered thru the human voice, helped contextualize analytic thought about water.

After our meditation, the group generated the map of factors to be addressed to connect the bioregional and environmental justice elements of Memphis and reveal a Trigger Point. The most striking comment was that racism is a significant impediment to progress, perhaps indicating that it might be the Trigger Point we must address to restore environmental health to the region. In response to a brief questionnaire distributed after the event, one respondent replied to the question:“Q: What did you learn?A: … insights into the inter connectedness of various forces at work.”

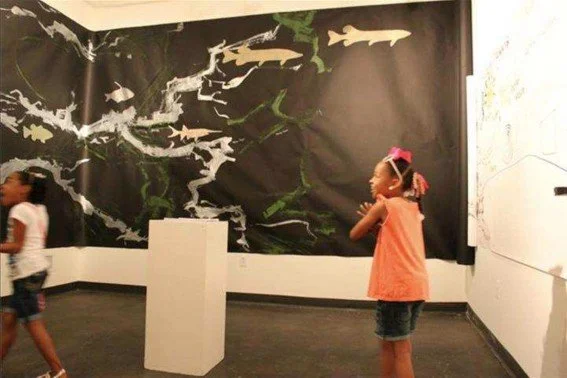

Fig. 3 Photo by Lester Merriweather - Installation detail from the Hyde Gallery, with audience, showing view of 107" x 432" painting of the local river systems and cut outs of endemic fish

The last phase of activity was a live webcast conversation, “Connecting the River Dots”16 with ecological art practitioners: curator Yvonne Senouf of M.E.L.D.,17 who spoke about endangered river systems in Athens, Greece; artist Eve Andree Laramee 18 who addressed radioactive hazards worldwide; artist Ruth Hardinger19 who presented the impacts of fracking on watershed; Fish Story team member Dr. Eugene Turner and myself.

This constellation of events was designed to ask how fish will survive the Anthropocene, the era when humans have come to dominate, every aspect of life on earth. Many scientists believe no living species has evolved to cope with this level of rapid change, and in fact, many species of fish are disappearing, some because of the indirect effects of warming waters (Eklöf et al. 2012). We are experiencing what I call, a “collapse of time,” since we entered the fast phase of climate change in 2010, forcing urgency upon us all. Many people respond to urgency with fight or flight but collaboration across disciplines and background is another option that may be equal to this collapse of time. Art and artists are trained to respond to circumstances with the speed of intuition. Scientists contribute insight based on quantifiable data. Working collaboratively, in a transdisciplinary manner with art and science, communities can pool knowledge bases and constituencies for greater resilience. In the Anthropocene, even racism may yield to knowledge.

Reference List

Journal Articles

Hilty J, Merenlende A (2000) Faunal indicator taxa selection for monitoring ecosystem health. Biol Cons J 92:185-197

Rahmani A (2012) Mapping Trigger Point Theory as Aesthetic Activism. PJIM 2: 1-9

Newspaper Article

Koeppel F (2013) 'Memphis Social' Vast project spans breadth of city's arts scene. The Commercial Appeal [Memphis] 1M and 4M

Articles by DOI

Burkholder J, Libra B, Peter W, Heathcote S, Kolpin D, Thorne PS, and Wichman M (2007) Impacts of Waste from Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations on Water Quality Environmental Health Perspectives 115: 308–312. doi:10.1289/ehp.8839"

Eklöf JS, Alsterberg C, Havenhand JN, Sundbäck K, Wood HL, Gamfeldt L (2012) Experimental climate change weakens the insurance effect of biodiversity. Ecol Lett 8:864-72. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01810.x

Books

Brown DC (2011) King Cotton in Modern America: A Cultural, Political, and Economic History Since 1945. Univ. Press of Mississippi, Mississippi

Dewey J (1938) Experience and Education. Kappa Delta Pi, New York Nicolescu, B (2008) Transdisciplinarity: Theory and Practice. Hampton Press, New York

Online Documents

Gibbs LI, Holloway CF (2013) NYC Hurricane Sandy After Action Report. http://www.nyc.gov/html/recovery/downloads/pdf/sandy_aar_5.2.13.pdf Accessed 05 August 2013

Silverstein J (2013) What Is the Health Impact of Fracking? PLOS Blogs http://blogs.plos.org/publichealth/2013/06/18/what-is-the-health-impact-of- fracking/ Accessed 05 August 2013